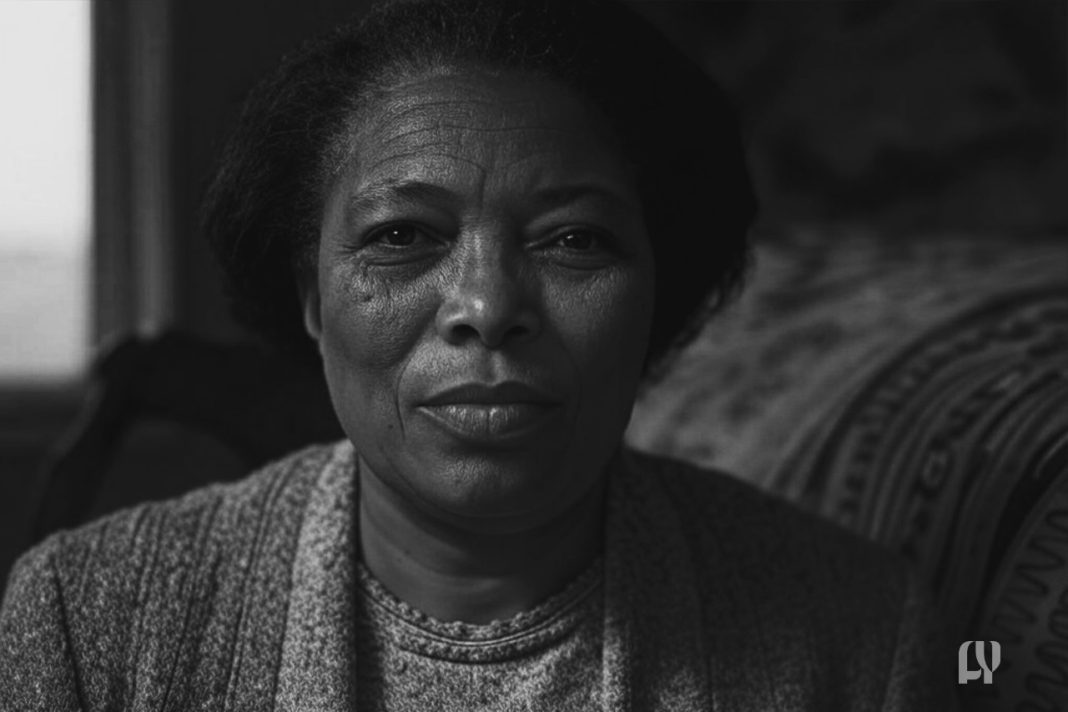

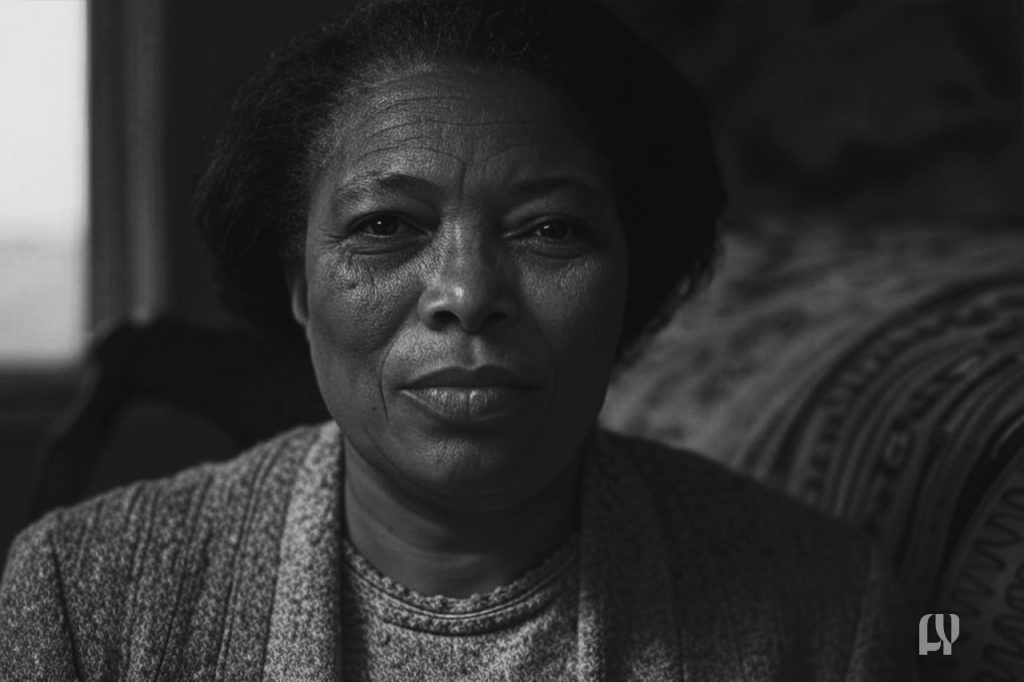

Zora Neale Hurston: A Legacy of Fire, Folklore, and Unflinching Truth

The Woman Who Walked with Stories

On the dusty roads of Eatonville, Florida, a girl once spun tales under the Southern sun. Eatonville is one of America’s first self-governed Black towns. Her voice was sharp as a blues note and warm as cornbread. Decades later, Zora Neale Hurston’ words still dance across continents. Her legacy is a torch passed to writers, thinkers, and dreamers from Harlem to Soweto. She died in poverty in 1960. Yet, her recognition in the 1970s solidified her status as a titan of Black literature. She became a guardian of folklore. She was a woman who refused to shrink her truth for the comfort of others. This is the story of a legacy that refused to be buried.

- Chapter 1: Roots in Eatonville—“The “Town That Freedom Built”

- Chapter 2: “Jumping at the Sun” – Harlem and the Anthropologist’s Eye

- Chapter 3: Novels That “Sang—“Their Eyes Were Watching God” and Beyond

- Chapter 4: The Struggles—“No “Mountain High Enough”

- Chapter 5: Resurrection—Alice Walker and the Rediscovery

- Chapter 6: “Legacy—“Sankofa” and the Eternal Flame

- Epilogue: The Pear Tree Still Blooms

- FAQ: Zora Neale Hurston Legacy

Chapter 1: Roots in Eatonville—“The “Town That Freedom Built”

Zora Neale Hurston was born in 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, but her heart took root in Eatonville, Florida. At three, her family moved to this thriving Black enclave, where her father became mayor. Eatonville wasn’t just a hometown—it was her first muse. Here, Black life flourished unapologetically. Children laughed in streets free of Jim Crow’s shadow. Women traded stories on porches. Preachers’ Sunday sermons shook the pines. This world taught Zora that Blackness was not a burden but a birthright.

I have been in Sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots.

But at 13, tragedy struck. Her mother’s death fractured her world. Her father remarried swiftly, and Zora, deemed “too spirited,” was sent away. She worked as a maid, a wardrobe girl in travelling theatres, and clung to education like a lifeline. By 26, she pretended to be 16 to finish high school—a lie that symbolised her defiance. Eatonville’s spirit was proud, resilient, and communal. This spirit would later pulse through her novels. It reminded readers that joy could bloom even in soil salted by sorrow.

Chapter 2: “Jumping at the Sun” – Harlem and the Anthropologist’s Eye

In the 1920s, Hurston landed in Harlem, New York. It was during the Renaissance—an era when Black art, music, and intellect exploded like fireworks. She became the “Queen of the Renaissance,” her wit as dazzling as her hats. But Zora wasn’t content with just parties. At Barnard College, she studied anthropology under Franz Boas, a pioneer in the field. Boas urged her to document Black folklore, a task others dismissed as “old folks’ superstitions.”

Armed with a notebook and pistol (for backroad safety), Zora trekked through the rural South and the Caribbean. In New Orleans, she danced in Hoodoo rituals. In Haiti, she recorded Vodou chants. In Florida, she sat with Cudjo Lewis, the last survivor of the Clotilda, the final slave ship to America. Their interviews became Barracoon. This was a raw, unvarnished account of Cudjo’s life. It was a work too bold for publishers in 1931. It was finally released in 2018.

“Folklore is the boiled-down juice of human living,” she wrote. For Zora, these stories weren’t relics—they were lifelines, proof that Black culture was rich, complex, and worthy of study.

Chapter 3: Novels That “Sang—“Their Eyes Were Watching God” and Beyond

In 1937, Hurston published her magnum opus, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Janie Crawford, the protagonist, wasn’t a tragic “race victim” but a woman hungry for love and self-discovery. The novel was written in dialect. This is clear in phrases. One example is “Ah wants things sweet wid mah marriage lak when you sit under a pear tree…”. Peers like Richard Wright criticised it for its “minstrel” tone. But Zora defended Black Southern speech as lyrical and alive.

Today, Janie’s journey—through three marriages, hurricanes, and a relentless quest for autonomy—is a feminist blueprint. South African readers might see echoes of Miriam Tlali or Bessie Head in Janie’s resilience. They were women who carved freedom in spaces meant to stifle them.

Hurston’s other works were diverse. Mules and Men is a folklore collection. Tell My Horse discusses Haitian culture. They blended anthropology with storytelling. Even her “failed” novel, Seraph on the Suwanee, about white Southerners, proved her range—and her willingness to defy expectations.

Chapter 4: The Struggles—“No “Mountain High Enough”

Zora’s life was no fairy tale. Money troubles haunted her. She took odd jobs: maid, substitute teacher, even a Hollywood scriptwriter. Her political views alienated allies. She opposed school integration, arguing Black institutions deserved investment, not abandonment—a stance that baffled civil rights leaders.

Her 1948 arrest on false molestation charges (she was acquitted) tarnished her reputation. By the 1950s, she was out of print, working as a maid in Florida. In 1960, she died of heart disease, buried in an unmarked grave.

Folklore is the boiled-down juice of human living.

Yet, Zora’s struggles birthed her strength. She once wrote, “I have been in Sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots.” Her words, like her spirit, refused to be contained.

Chapter 5: Resurrection—Alice Walker and the Rediscovery

In 1973, a young Alice Walker trekked to Fort Pierce, Florida, placing a tombstone on Zora’s grave. The inscription: “A Genius of the South.” Walker’s essay, In Search of Zora Neale Hurston, reignited interest in her work. Suddenly, their eyes were on university syllabi, and Zora became a feminist icon.

Scholars unearthed her plays, essays, and radical ideas. Her anthropological work was hailed as groundbreaking. Black women writers—Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou—cited her as a foremother. In South Africa, her themes of identity and resistance resonated during apartheid’s twilight.

Chapter 6: “Legacy—“Sankofa” and the Eternal Flame

Zora’s legacy is a Sankofa bird: reaching back to move ahead. She taught us that folklore is history. That Black joy is revolutionary. That a woman’s voice, in dialect or defiance, is sacred.

- In Literature: From Toni Morrison’s magical realism to Yvonne Vera’s poetic prose, Zora’s influence spans oceans.

- In Anthropology: Her techniques—immersive, respectful—paved the way for oral historians like South Africa’s Gcina Mhlophe.

- In Feminism: Janie Crawford’s mantra (“You got to go there to know there”) inspires women to claim their journeys.

Even her flaws—stubbornness, contrarian politics—remind us that genius isn’t tidy.

Epilogue: The Pear Tree Still Blooms

Zora once wrote, “There are years that ask questions and years that answer.” Today, as her works are taught from Johannesburg to Jackson, her answers ring clear: Stories save. Culture endures. And a woman who walks with audacity leaves footprints for generations.

In Mzansi, storytelling is the heartbeat of our villages. Zora’s spirit feels familiar. It is a kindred voice saying, “Tell your truth, ntombazana. The world needs it.”

FAQ: Zora Neale Hurston Legacy

What is Zora Neale Hurston most famous for?

Zora Neale Hurston is renowned for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. This groundbreaking work celebrates Black womanhood and Southern culture. She is also celebrated for her anthropological work documenting African American and Caribbean folklore.

What happened to Zora Neale Hurston when she was 13?

At 13, Hurston’s mother passed away, and her father quickly remarried, sending her away from home. This period marked the beginning of her struggles with poverty and her relentless pursuit of education.

What did Zora Hurston struggle with?

Hurston struggled with financial instability throughout her life, often taking odd jobs to support herself. She also faced criticism for her political views and writing style, which alienated some peers and publishers.

What are 5 words that describe Zora Neale Hurston?

Five words that describe Zora Neale Hurston are bold, resilient, visionary, unapologetic, and trailblazing. Her life and work embody these qualities, leaving an indelible mark on literature and culture.

Why is Zora Neale Hurston important?

Zora Neale Hurston is important because she preserved Black folklore. She gave voice to Black Southern experiences through her writing. Her work continues to inspire generations of writers, anthropologists, and feminists worldwide.